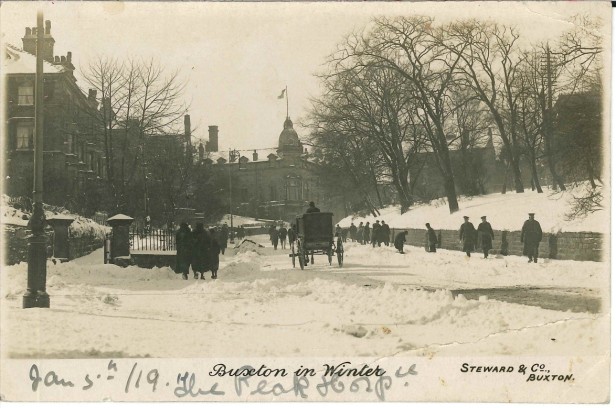

The building that Buxton Museum and Art Gallery is housed in has a varied past, beginning its existence as a spa hotel in the 1800s before becoming a museum in the 1920s. It also had a brief lesser-known role as a war hospital. Derbyshire Museums Manager Ros Westwood sheds light on this dim chapter of Peak Building’s history:

We are often asked about the role of this building in the First World War.

The museum was built in about 1875 as a hydropathic hotel, offering cold water treatments. By 1915 the Peak Hotel was (again) up for sale. The Canadian Red Cross Society secured a lease to establish the Canadian Red Cross Convalescent Hospital, No 2, Buxton

The Canadian Red Cross Hospital, Buxton opened in May 1916, under the command of Lt. Col. H.D. Johnson C.A.M.C. He would soon be relieved by Major F. Guest (later Lt. Col.) and in 1917, by Major F. Burnett DSO, who was also promoted. There were 11 officers on the staff, 35 nursing sisters and 101 other ranks. The nursing sisters had accommodation at Northwood, now part of the University of Derby campus, which became an annexe hospital in October 1917.

Amongst the doctors was Frederick G Banting, who would return to Canada after the war to continue research into diabetes and the use of insulin in its treatment, for which he was awarded the Nobel prize.

The hospital had 275 beds in rooms with central heating, its own electricity system and was on the town’s mains water. About 100 patients a month were treated, using the latest apparatus. This included swimming baths, warm mineral and vapour baths. Three quarters of the patients received therapeutic baths daily or on alternate days.

There was massage, mechanical vibration, high frequency apparatus, radiant heat, and cataphoresis electric cautery. Before the introduction of antibiotics this procedure was used to close wounds and stop infection. Research suggests it might not have been as effective as anticipated.

Of course, having easy access to drinking water from Buxton’s famous St Anne’s Well may also have been beneficial.

As a ‘special’ hospital, patients were admitted with a range of conditions many made worse from having been in the war zone on the Western Front. They were suffering with rheumatic fever, myalgia (which affects the muscles), neurasthenia (exhaustion of the nervous system), neuritis, osteitis (inflammation of bone), insomnia, arthritis, nephritis (kidney inflammation), functional diseases of the heart, neuralgia, certain kinds of gout and especially, shell shock.

Eventually in March 1919 the hospital was absorbed into the larger Granville Canadian Special Hospital, Buxton, which functioned in both the Buxton Spa and Empire Hotels. The hospitals were all closed during that year. By then almost 3,300 people had received treatment in this building.

I am grateful to a researcher by an MA student at the University of Ottawa with access to the archives in Canada who has turned up this fascinating information.

Reblogged this on Derbyshire Record Office and commented:

A hundred years ago this year, the building that now houses Buxton Museum was just winding up as a military hospital for Canadian First World War servicemen. Buxton Museum have just posted some fascinating new research about the museum’s hospital years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My grandfather Dr. KMB Simon served during WW1 at the Granville Army Canadian Hospital. I was wondering if you might have any references on him? I am doing ancestry family research and would appreciate any help. Thank you. Lorraine Brooks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Ms Brooks

I’m a Canadian, living in Buxton, very interested in the Canadian Red Cross Hospital during WW1, and the burials in the cemetery here.

Today I visited the cemetery, and having taken a photo of a gravestone of a death in February 1919, I’ve accessed the file on this serviceman – with your grandfather’s signature. Coincidence. How is your research proceeding?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for responding to Ms Brooks’ request, and for sharing information from your research.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My Grandfather, Private James Albert Smith was with the 84th Battalion and was wounded at Regina Trench on November 18, 1916. He was hospitalized at Buxton before being discharged to Toronto on March 28, 1918. He returned home a changed man who would lash out at his children (my Father being one who was “kicked” out at 14). I never understood the reasons why my Grandfather was like this until discovering that he was wounded at the Battle of the Somme. I then realized that he probably suffered PTSD. I am anxious to know all I can about where and what the conditions were like at the hospital. I am sure while in the hospital, my Grandfather met a nurse but returned to his wife and family. When his wife died in 1939, he married Constance Thompson from England. He died in 1949 of a massive stroke and she returned to England with everything. No one in the family ever heard from her again.

LikeLike

Thanks for adding to the story, Barbara. It’s great to shine more light on this largely unknown part of Buxton’s history.

LikeLike

Hi Barbara!

Just happened upon your comment. If you’re still interested, the war diaries of the Canadian Red Cross X Special Hospital have been digitized on Library and Archives Canada. Here are the links:

1916 – 1917:

https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?app=FonAndCol&IdNumber=2005143

1917 – 1919

https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?app=FonAndCol&IdNumber=2005144

NOTE: there were many Canadian hospitals based in Buxton and the surrounding area. If you’re not sure that it was the Special Hospital, try looking for the Granville’s war diaries (also available online)

LikeLike

You are most kind and I will follow up on your suggested link.

LikeLike

My Grandfather was wounded and was suffering from continuous pain and sever nervousness from Shell shock, looks like he may have been admitted May 20th 1919 for therapeutic treatment before his return to Canada.

LikeLike

I’ve learned from Canadian war records that my great-great-aunt Lillian Annie Garrard was a CAMC nurse in Buxton from November 1917 to August 1919. Remarkable to think she’d have worked alongside the great Frederick Banting, whose name is on the most prestigious Canadian academic awards today. I’d love to learn any more that others turn up about this facility.

LikeLike

Thanks, Gregory. It’s a part of local history that we’re learning more and more about all the time.

LikeLike

Hello would anyone know of a Henry Charles Triggs, 37. C.R.E. Engineer. Canadian Special Hospital, Buxton. 1916. Married Annie Bosson 4 Nov 1916. Father John Triggs, Retired Builder. He signed Registry Charles Henry Triggs. If he is the Charles Henry some people have on Ancestry marrying Annie Bosson he was already married with Children. Different birth dates. Thank you for any help you may be able to give me.

LikeLike

Hello would anyone know of a Henry Charles Triggs, 37. C.R.E. Engineer. Canadian Special Hospital, Buxton. 1916. Married Annie Bosson 4 Nov 1916. Father John Triggs, Retired Builder. He signed Registry Charles Henry Triggs. If he is the Charles Henry some people have on Ancestry marrying Annie Bosson he was already married with Children. Different birth dates. Thank you for any help you may be able to give me.

LikeLike

Hello Jennifer. Unfortunately we do not have any records at the museum for any of the soldiers and staff who worked at the building when it was a hospital. We would recommend contacting the Canadian Military Records: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/contact-us/military-records.html

or try this site: https://ca.forces-war-records.com/canadian-military-service-records/

LikeLike

Hello

My Grandfather, Thomas Harold Rowbottom, was wounded in August, just after defending Vimy Ridge. He was sent first to Oprington Kent and then to Buxton where he became a member of the band/orchestra there for a time before being sent home to Canada. It was an 80 piece band with a leader by the name of Bill — Legate? Legett? — who played trumpet. He and this man Bill also played the circuit, including the Opera House. I have some of the other names of other players but no other information. I would very much appreciate it if someone could point me to a website, if such a thing exists, where I might find more information or could at least provide me with the proper spelling of this man’s last name. I am compiling all of my grandfather’s tape recordings, notebooks and other document to be made public, at some point, and would like to give Bill the respect that he deserves. I am afraid that the only information in the family archive is via a tape recorded memoir.

Thank you

Sherry Rowley

LikeLike

Thanks for the information, Sherry, we’ll see what we can find out. We’ll be in touch asap.

LikeLike